I met Vera when she joined the staff of the midwifery clinic where I worked. Patient demographics had changed drastically over the preceding year, forcing a kicking and screaming administration to advertise for a translator. Vera was a fifty-something, bottle-born redhead with a personality to match. She was also Puerto Rican, which would seem to make her a perfect fit, unless you know something about the importance of dialect to the Spanish language. Most of our patients had immigrated from Mexico and Central America. Watching her with them reminded me of a comment my son made, after his first football practice, when he described a coach who had just moved to Atlanta from New York as, “…that French guy.”

Vera persevered, undaunted. She never lost patience with patients whose pronunciation differed from hers. But neither did she change. She taught, instead.

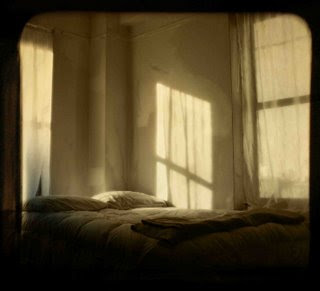

As I would soon learn, Vera was well schooled in adversity. One year before joining our staff she buried her husband of nearly thirty years. He had suffered from ALS for the preceding ten. During the two years we worked together, she constructed a story of undying love and amazing perseverance. She talked about the kind of man he was before the illness, the adventures he’d lived for, and their passion. He had been a successful businessman, making pots of money right up until the day his legs refused to support him. His time in a wheelchair was short, as the disease progressed quickly. Soon their world shrunk to fit inside their sumptuously decorated master bedroom. Vera slept by her man every night until his last night, and on his last day wrapped her body around his as he breathed his last breath.

Her description of his losses struck me. I pictured them as she spoke. One day he couldn’t write with his left hand. Six months later he couldn’t raise his arm to put on a t-shirt. The other arm quickly followed suit. He fell a lot before his legs stopped working. The wheelchair meant she couldn’t leave him for long. One side of his mouth went limp, so she had to remember to put the spoon in the other side or the food would fall out, making him angry.

I could easily picture myself the caretaker. I graduated from nursing school. I worked as a staff nurse for two years before quitting to care for my own babies. I volunteered at a hospice.

What I can not imagine is being the one with the misshapen mouth.

Years later, I discussed this with a friend who sympathized, saying she and her husband had had “the discussion”. She almost whispered the words, and I understood. Saying them aloud makes them real.

“I won’t have anyone taking care of me. When the time comes when I can’t take care of myself, that’s it, I want to go.”

“You mean…?”, I ventured.

“Yep.” The word felt incongruously nonchalant. “And, he’s going to help!” It was more an order than a suggestion. I found myself feeling sorry for her husband. Will he still be afraid of her? Even when she’s dying?

I watched my mother live four years as a cancer “survivor”. And, that’s what she was; she was surviving. You certainly couldn’t call it living, because it in no way resembled her life before cancer. Life after cancer was dependent on a steel oxygen tank and lots of plastic tubing. Oh, and yogurt. Radiation killed her natural flora, making digestion difficult. Yogurt helped to replenish it, allowing her to eat very small amounts of other foods. And, she developed a penchant for scarves…

She smiled a lot. To hear my father tell it, she and he enjoyed those years very much. But I have to wonder. I wish I’d asked.

“If you had it to do all over again, would you?”

I heard an interview today with Tony Judt. You may not recognize the name. He was a British-born historian who wrote what he called “boring old history books”. One of them was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize. He died last Friday from complications of ALS.

The interview was taped five months ago. His voice was digitally amplified and yet hard to hear over the wheezing oxygen pump next to his chair.

The interviewer focused her questions on death and dying, asking how things had changed for Mr. Judt, and how he felt about them. The topic turned to religion. Mr. Judt was a Jewish man who attended temple to please his wife.

He began by talking about life in a wheelchair, moving on to the time when his life shrunk to fit inside his bedroom. He painted a picture of life lived in an empty space that people used to visit. He felt sorry for himself until he realized it was his responsibility to be present, to be joyful, to create memories, because memories are after-life, and soon after-life was all the life he would have. In Mr. Judt’s opinion, we live on in the minds of our loved ones. How we live is up to us.

Boiled down, it’s selfish versus selfless. Selfish won’t allow for less than. Selfless accepts less than and builds upon it in order to leave something behind.

I never met Mr. Judt while he was alive. Now, six days after his death he’s left me with something to think about.

Perhaps he was right…

© Copyright 2007-2010 Stacye Carroll All Rights Reserved

No comments:

Post a Comment